The Palaces of Memory

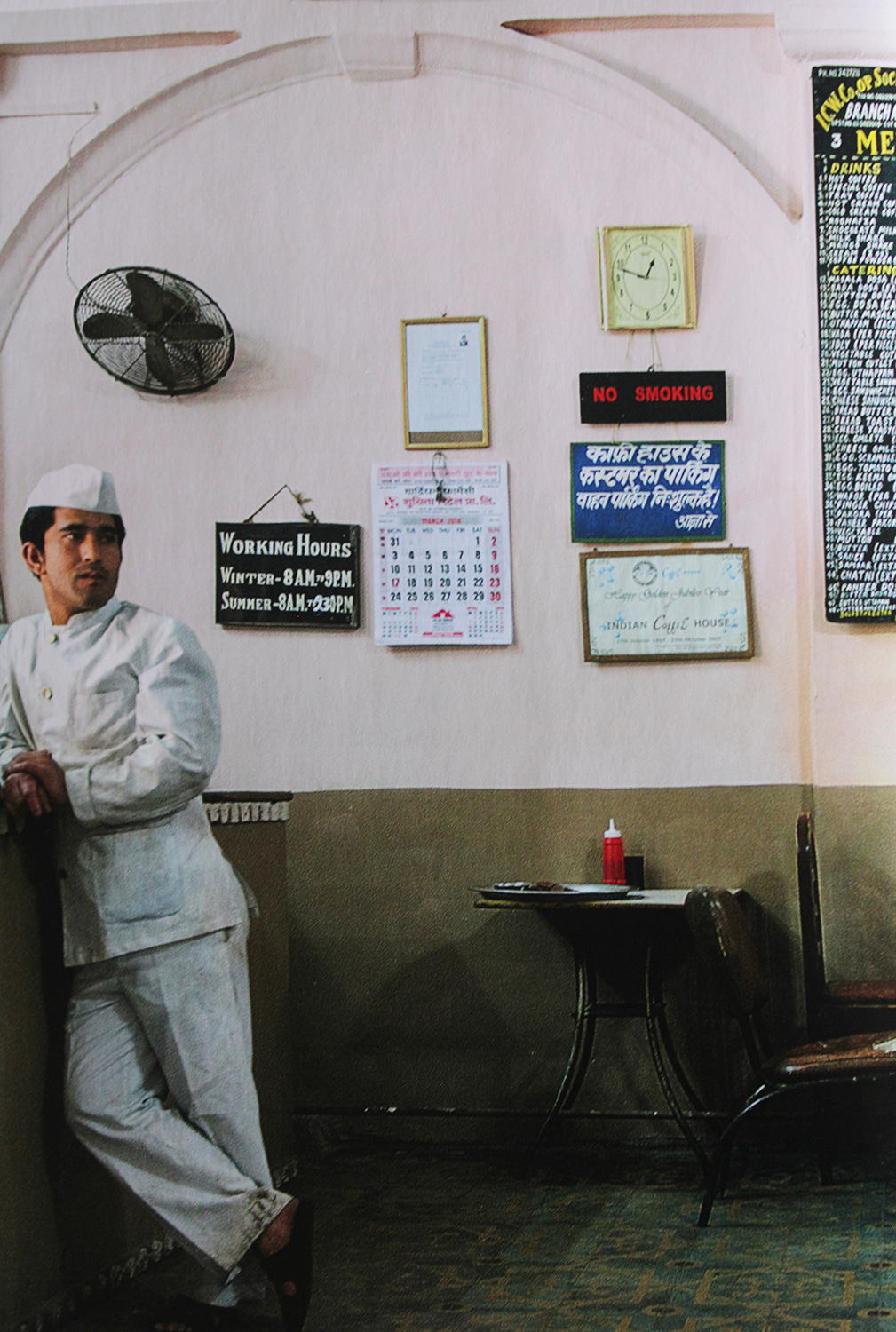

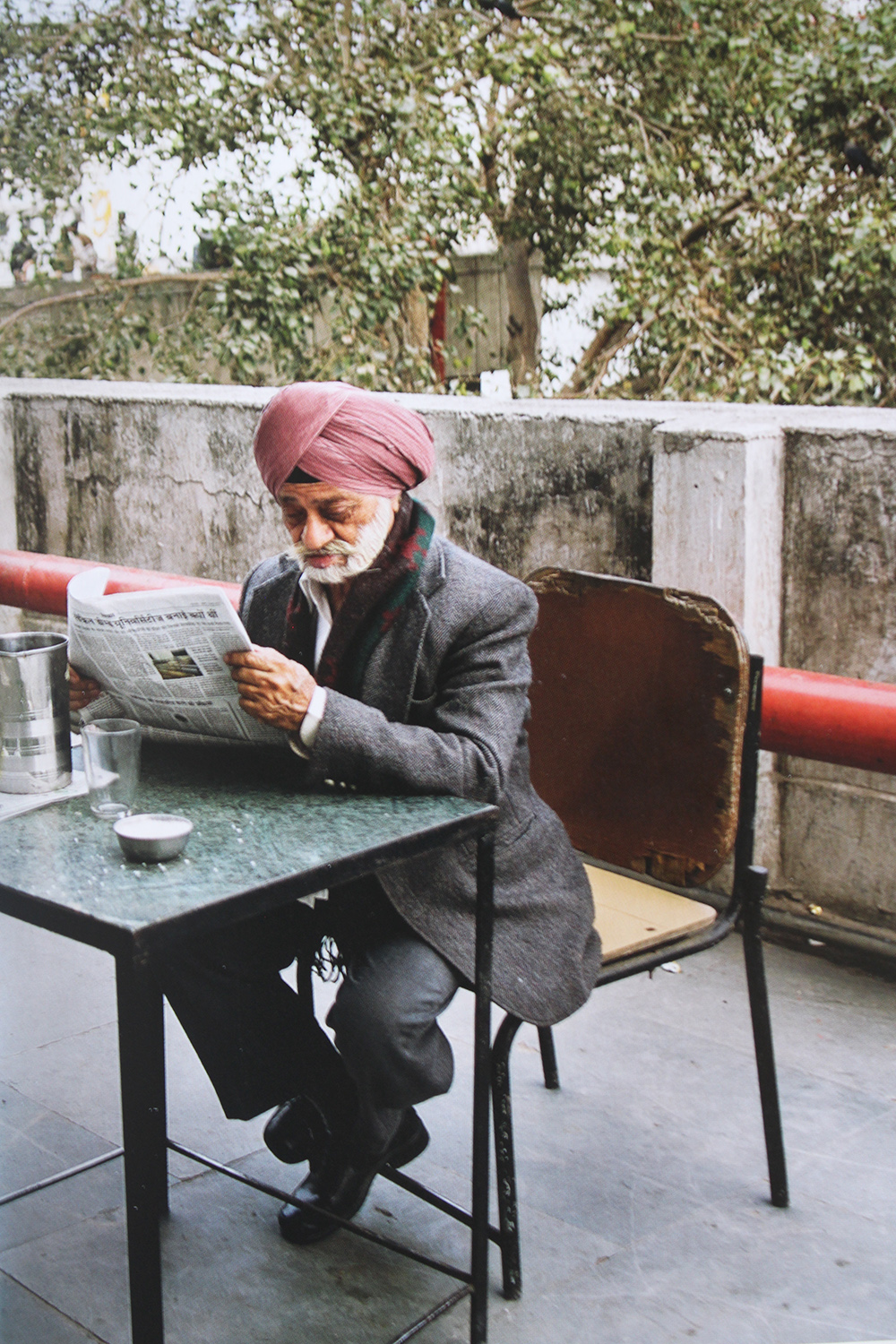

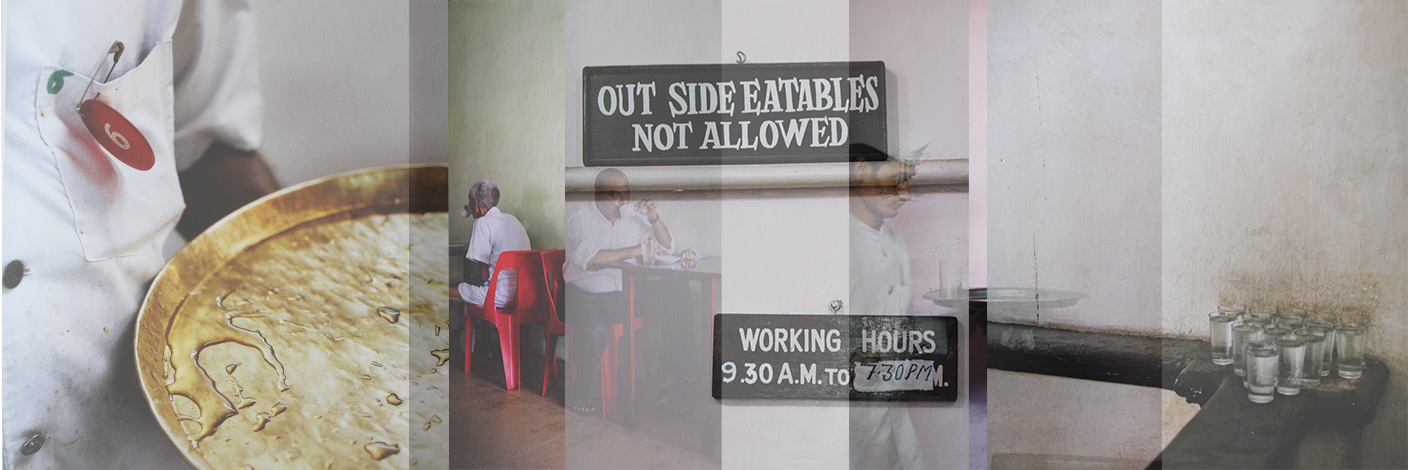

This is a book I discovered late and by chance. I was led to it by a picture found online while researching design possibilities for a coffee shop in Shillong. One intriguing photograph lead to more and soon I was placing an order for The Palace Of Memories by Stuart Freedman. The book is a poignant photo essay into the heart of the coffee houses of India, a chain run by series of worker co-operative societies. An Indian Coffee House is the very antithesis of trendy and is better known to be a hub for discussion and debate, the thinking ground for socialist and communist movements. I’ve personally visited the ones in Delhi and Calcutta on occasion and usually return for the environment — it is comforting to be in a place with links to the past and more so one that’s unpretentious. The Indian coffee house is not focussed on being fashionable nor has it been interior designed to create a certain ambience for commercial purposes. It is an easily accepting space with an air of nonchalance — a living repository of the past. The Palace Of Memories captures this beautifully through text and visuals. It opens with the words and thoughts of Amit Chaudhuri and closes with those of Stuart Freedman. Between them is a poetic photographic rendition of the people and things that inhabit the coffee houses. I leave you with some pictures from the book and the words of Chaudhuri.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————–

To understand shabbiness – its colours and its perfume – one has to understand modernity. One has also to comprehend the aesthetics of socialism, and the morality of what’s loosely called the Nehruvian age. Modernity is a paradox: ‘modern’ means ‘recent’ or ‘new’, but the most powerful cultural expressions of modernity involve a love – maybe an indiscriminate love – of the unfinished, and of surfaces from which the shine is peeling off. This is an emotion, or position, that’s difficult to defend rationally. But that hasn’t prevented writers from constructing precisely such a defence, sometimes even in nationalistic and political terms. Junichiro Tanizaki spoke of the Japanese/ Chinese/ Asian adoration of the signs of ageing, the acculturated ‘patina’, as being opposed to the Western devotion to glowing objects and clean surfaces: “Chinese food is now most often served on tableware made of tin, a material the Chinese could only admire for the patina it acquires. When new it resembles aluminium and is not particularly attractive; only after long use brings some of the elegance of age is it at all acceptable. Then, as the surface darkens, the line of verse etched upon it gives a final touch of perfection. In the hands of the Chinese, this flimsy, glittering metal takes on a profound and somber dignity akin to that of their red unglazed pottery.”

Tanizaki pretends that the opposition here has to do with the traditional and the new, the Chinese and the Western. The truth is that the case he makes is a modernist one. It’s at the core of a sensibility that’s expressed itself with vigour from the early 20th century onwards, and one of its concerns is to rearticulate one’s relationship with history (or with the past). Neither history nor the past presents itself to the modern as a complete phase that’s long over, but as an air of dereliction, a cluster of stains and signatures that is, in some ways, indistinguishable from the present and from the modern’s habitations, from his or her favourite haunts. This sensibility has fewer proponents today than it did once, but there are some artists, like the poet Anne Carson, who are still trying to define its excitements: “In surfaces, perfection is less interesting. For instance, a page with a poem on it is less attractive than a page with a poem on it and some tea stains. Because the tea stains add a bit of history. It’s a historical attitude. After all, texts of ancient Greeks come to us in wreckage and I admire that…” Carson, besides being a poet, is a classical scholar. Much of her poetry comprises an updating of the ‘texts of ancient Greeks’. Here, speaking to the Paris Review interviewer, she’s pointing out that the classics are never pristine in their availability; they come to us, figuratively and physically, in fragments and pieces, in poor condition, as ‘wreckage’. To be drawn to this process of slow disappearance – rather than just to read the classics – is fundamental to the ‘historical attitude’. It is what makes the ‘page with a poem and some tea stains’ on it attractive to a particular kind of reader: history not as knowledge, information, and fact, but as an assignation of meaning to shabbiness.

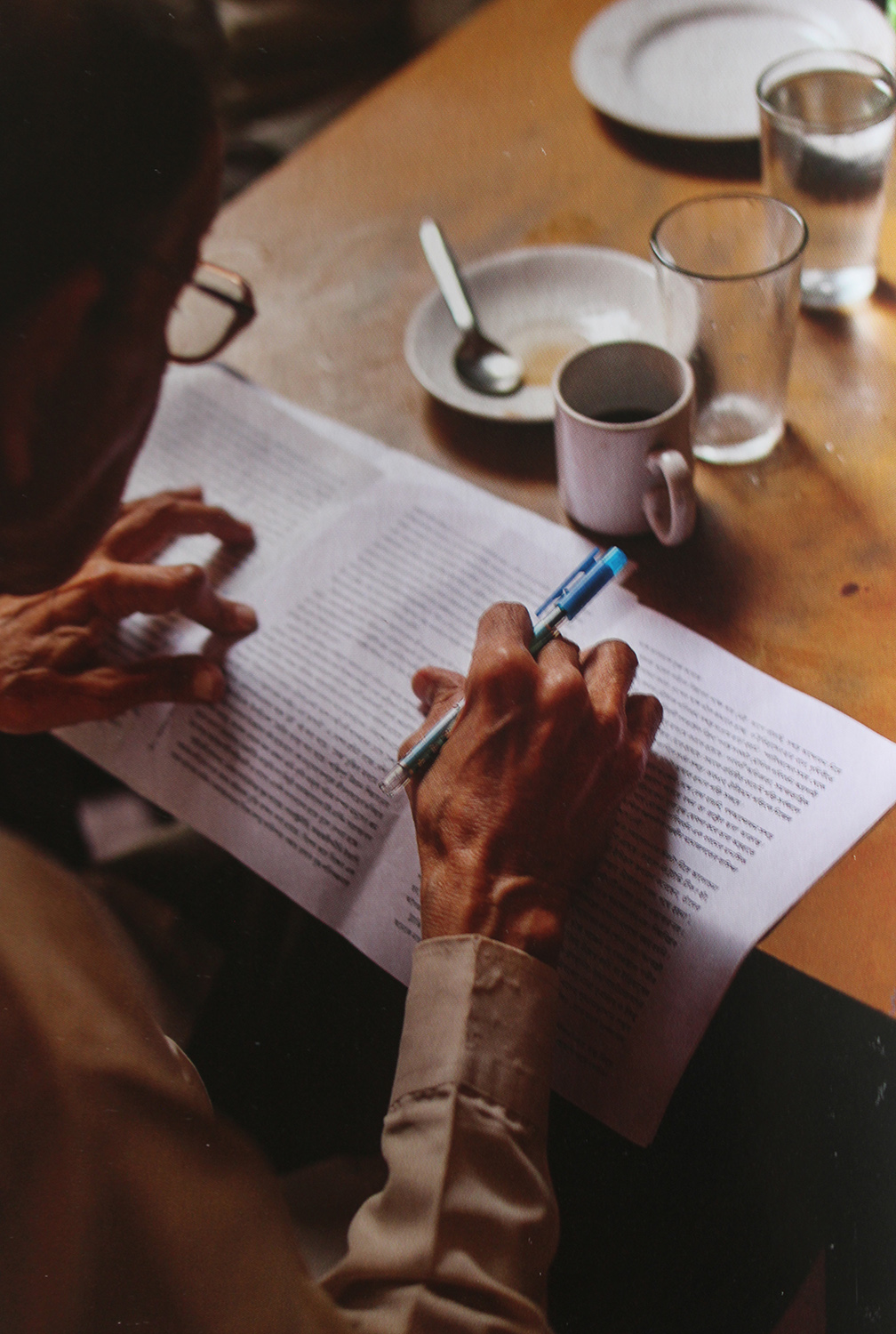

Modernity, in its aura of shabbiness (which came to it from the effects of industrialization), reminded us of its participation in history: it was new, but also vanishing. It seemed to be constantly dying. Some of its smells were invigorating – but rarely life-giving. For instance, cigarette smoke: it’s fallen out of favour, and now encountered only in secret or quarantined places. It’s associated, subliminally, with the self-destructive impulses of the modern, and the modern’s fascination with history as wreckage. Then there’s petrol: its sweet, powerful, unsettling fragrance. Coffee might be added to this list: a smell that’s perpetually strange, even foreign. The fragrance of coffee beans is one of the most magical I know, but its associations are ambiguous. Coffee is not a drink that can be embraced fully. Like shabbiness and Anne Carson’s ‘historical attitude’, it’s a particular kind of taste and addiction. Its domain, like the coffee houses in which we once found and imbibed it, is the domain of a specific and eccentric sensibility. The air of lassitude in these places, the stains on the table, are as important to the ‘historical attitude’ of the coffee drinker as the coffee itself. In the last two decades, coffee has been rescued from this ambivalence by gentrification, by the great coffee chains. Starbucks, Costa Coffee, Caffè Nero, and the Indian Café Coffee Day or Barista – all these curate the taste of coffee, but eschew (perhaps liberate us from) the ‘historical attitude’ of the modern.

How do we situate the coffee house in India? For that matter, how do we situate shabbiness here? The task is a slippery one, because the taste for the frayed, the derelict, and the unfinished is barely acknowledged in relation to India, let alone categorized. This, I suppose, is true of the culture of shabbiness in any ‘third world’ nation – that it must be subsumed in the narrative of underdevelopment. Today, especially, when the allocation of the globalized world into ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ countries is hardly questioned or scrutinized, the unfinished or the decaying must, in certain nations, always be seen to be a feature of underdevelopment (which progress will one day remove) rather than being – at least in some quarters in those societies – a strategically cultivated ethos.